Moisey and the story he couldn’t tell

Before there was Corona and the war, hundreds of visitors would come to Ukraine each year with Christians for Israel to meet the Jewish communities. The small town of Tulchin was always part of the program, where Rita would share how she survived the Pechora death camp. She spoke for a whole generation of imprisoned children who had never been able to articulate the horrors they experienced. Among them is Moisey, who is still regularly visited by our team.

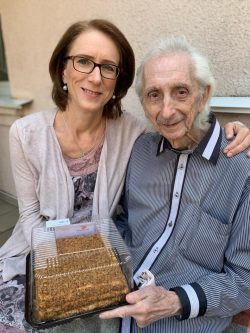

No sooner have we entered the gate, and Moisey welcomes us. His wife has turned the courtyard into a small botanical garden. Moisey is delighted with the cake, his wife with the flowers. The most important thing for both of them is that they are not forgotten. That someone sits next to them on the garden bench and brings greetings from Christians all over the world.

Moisey lives with his family – his wife and disabled daughter – in Tulchin, a small Ukrainian town near Vinnitsa. Tulchin was once well known – the Polish Count Potocki brought the town – and the Jewish life in it – to prosperity at the end of the 18th century. There were more than 10,000 Jewish residents, 18 prayer houses and 70 Jewish schools before the October Revolution and the following pogroms decimated the population and the Soviet regime drove religious life underground. When the Wehrmacht invaded in the summer of 1941, Tulchin’s Jewish community was still the largest in the region, with 5,600 members.

“Dad was a shoicher, a kosher butcher. His name was Naum,” Moisey tells us. “He came from a big family – three brothers and six sisters. Mom’s name was Riva, from Rebekka; she was a seamstress. I was two at the time.” Moisey will never tell us exactly what happened next. He can’t share it – not even after 80 years.

Infected with typhus

Most of what we know about the Jews of Tulchin we learned from Rita, Rita Schweibes. She was three years older than Moisey and she memorized everything. The ghetto came with the Germans. After months of humiliation and violence, the town’s Jews were taken to the Jewish school at the beginning of December.

“We were held there for three days,” Rita recalled. “There was a Ukrainian doctor, Beretzki was his name. He gave us injections. Syringes with typhus pathogens. Then we had to take a shower. When we came out again and looked for our clothes, they were soaked and covered in lice – so that the typhus would spread faster. Then they drove us on the death march.”

Moisey’s mother was also there, with her little “Mosik” in her arms. And the other family members? Moisey begs us not to ask any further, tears welling up in his eyes.

The road to death

In all, an estimated 12,000 Jews from across the region were divided into three groups during the Advent weeks of that freezing December, then herded along by German Einsatzgruppen and Ukrainian police with German shepherds.

“We had to walk, walk, walk,” Rita recalled. “Twenty kilometres on the first day. Many of the elderly collapsed on the way; they were shot on the spot. That’s why it’s called the ‘road of death’.”

In the evening, the survivors of the first day’s march reached the village of Torkiv, where they had to spend the night huddled together in a horse stable. “Some of them lost their minds,” said Rita. “We had nothing – nothing to eat, nothing to drink, nothing to relieve ourselves. When it was light again, many had hanged themselves from the ropes intended for the cattle”.

Pechora – the “death snare”

After another day’s march, the Jews from Tulchin arrived in Pechora on the evening of December 8, 1941. A pretty little village on the edge of the forest, with a large sanatorium. Surrounded by a wall on three sides and bordered by the Bug River on the fourth, the territory of the sanatorium became a death camp overnight, known as the “death snare”. Historians would classify it as the most cruel concentration camp in the Romanian-occupied part of Ukraine – although only few gunshots were fired here. The prisoners were simply left to the elements without any provisions.

Moisey does reveal a few sentences about the camp. “It was terrible in winter: snow, ice and bitter cold. The whole area was overcrowded with people huddled on the ground. Many got typhus and dysentery; fever and scabies were omnipresent. People were constantly looking for something to eat. People traded their clothes for it. They even fought over a few stalks of grass.”

The only chance of survival was to get out and beg from time to time. “There were different guards,” Rita reported. “When Rushilo was on shift, he let us children out. There were others, like Smetanski, who were cruel and beat the children to death. There was only the river to get water. The Bug was the border to the German zone. On the other bank, the soldiers played the harmonica. If anyone from the camp managed to get near the river, they would have a shooting competition, just for the fun of it.”

Unspeakable horror in front of children’s eyes

While some died, new groups of Jews were constantly being deported to the camp – from Bukovina, Romania and Bessarabia. They were somewhat wealthier and were able to survive for a while by bartering.

Rita and Moisey soon had no family left. They had nothing to barter with the villagers at the fence. Their bellies were bloated with hunger. Every now and then, someone would slip them something through the fence – a red turnip, a few potato peelings, a potato sack to cover themselves.

They saw how small children were grabbed by the legs and beaten against a tree; how their mothers collapsed next to them and the children’s corpses lay there for a long time. They saw how prisoners who had tried to escape were beaten to death by the guards at the entrance gate. They were there when everyone had to line up at the well: old people and children on one side, young workers on the other. The latter never came back – whenever a group had completed a section of the new road to Voronovitsa, they would be shot and buried under the road surface.

There was a larger building – incomprehensibly still used as a sanatorium today. The prisoners sought refuge there. “Every morning, the guards went through the rooms and carried the bodies out,” Moisey remembers. “We almost froze to death in winter and died of thirst in summer. There was nowhere to go. Even if someone escaped, they were usually handed over. The Germans were everywhere.”

The day of liberation

Tens of thousands of murdered people lie in mass graves in the nearby forest. No one has exact figures. There are no photographs of the camp. On the day of liberation, 14 March 1944, 330 Jews, mostly children, were still alive.

“The Nazis left so quickly that they didn’t get around to killing us all,” says Rita. “We had all barricaded ourselves in the morgue,” Rita continued. “When the knock came, we were afraid to open the door. But then we heard: ‘It’s us, the Red Army! We’ve come to free you!’ Cautiously we opened the door. We couldn’t believe our luck. We kissed the soldiers and the horses. Some of us fainted.”

Eight-year-old Rita ran back to Tulchin on foot, the way she had come. But there was no home for her and no family left. Desperate, she decided to drown herself in the river. A Ukrainian woman saved her. Rita went on to become a midwife, helping thousands of Ukrainian babies to be born.

Rita’s promise

Rita would tell her story to each of our groups that came to Ukraine for a working trip. We would stand with her in the garage in Tulchin where she stored our food parcels for her small community; then we’d stand in the mud at the horse stables in Torkiv, in the icy wind at the gates of the death camp, at the mass graves overgrown with bluebells in the forest clearing where Rita would always speak to her mother in Yiddish and cry.

“It’s hard for me to talk about it; I re-live it all each time and then I don’t sleep for several nights,” Rita once told us. “But I made a promise back then, in the death camp, where I thought every day that it would be my last. ‘Almighty God,’ I said, ‘if I survive, I will tell everyone what I have seen here.’”

Rita kept her promise for the rest of her life. She did it for a whole generation – for her friend Raya and for Moisey, who could not find the words to tell of all the horrors they had seen. A few hours before she went home to be with the God she had trusted all her life, our team was able to be with her and thank her for all she had passed on to us.

Rita has completed her difficult calling. Raya followed her a few weeks later. Moisey is still around. Whenever we are in the neighborhood, we visit him. We sit with him and his wife on the garden bench and drink a glass L’chaim, “To life!” On May 9, we will congratulate him on the fact that 80 years ago the war was over, and Jews were allowed to live again.