Talmud for Everyone

Every few hundred years a great Jewish scholar arises whose works, opinions and teachings impact both secular and religious Jews. The prolific author and commentator, Jerusalem-born Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz – was one such man. Even though his father was a great grandson to a famous Hasidic rabbi, his father chose to be an atheist communist. In the 1930’s he fought in the paramilitary and controversial Stern Gang and even set out to Spain to do his part for the Civil War.

As a teenager in 1950’s largely secular Israel and coming from a secular home, against all odds Adin chose to be an observant Jew. In one of his later interviews he interestingly explained this step stating that because he was an inherently skeptical person, he had always questioned the viability of atheism.

In addition to rabbinical studies, Adin also studied math, physics, and chemistry. Following graduation, he even set up several experimental (and ultimately unsuccessful) schools in the Negev desert to start a neo-Hassidic community. At the tender age of 24, he became the youngest school principal in Israeli history – a record he still holds today just a year after his death.

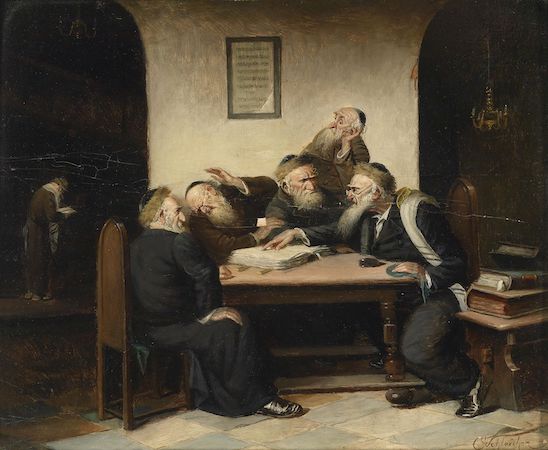

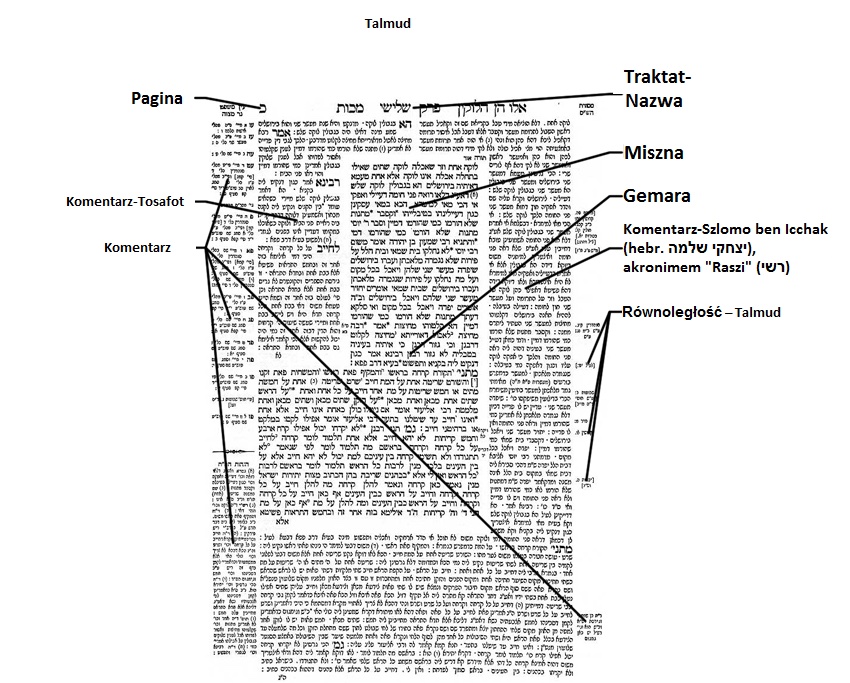

His knowledge was vast. Throughout his life he authored a massive 60 books and produced commentaries on the entirety of the Tanakh, but mostly he is cherished and remembered for his groundbreaking work of translating the Babylonian Talmud. The Talmud is a vast work which has 2,711 double-sided pages. In Aramaic, the lingua franca of that day, it records hundreds of years of rabbinical debates that took place 1800 years ago in Jewish seminaries in ancient Babylon.

“Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz is cherished and remembered for his groundbreaking work of translating the Babylonian Talmud”

By translating the Talmud into Hebrew, he took this Aramaic text out of the exclusivity of the seminaries of the learned and made the inaccessible accessible to the secular and religious Jew. With a new access to the text, Jewish people from all over the world began to study it and make it their own again.

Adin began this life work in 1965, at the young age of 27. Forty-five volumes and forty-five years later, he finally finished it. When the volumes are stood side by side they reach over 6 meters long. His work has been translated by publishers into English, French, Russian and Spanish. In a famous interview given to the New York Times, he said that his purpose was to “accommodate even beginners with the lowest level of knowledge.” Clearly he wanted to substitute a dusty book for a living teacher. Adin’s scholarly importance has been compared to that of the two most influential and greatest Jewish scholars in “recent” history: the medieval Rashi and Rambam.

“Sometimes it is better not to know too much about the difficulties because it helps focus on the possibilities”

Critics and fans all attribute to him the revolutionizing of the Jewish landscape. This he has done well, and not just through writing books. During the persecution of Jews under the former Soviet Union, he travelled there regularly until he was ultimately able to found the Jewish University, (the first degree-granting institution of Jewish studies in Communist Russia) in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. His travels also took him to the Vatican, where he had a private audience with Pope Francis.

Alongside his scholarship, the popular Rabbi who died in 2020, will also be remembered for his humility. Since he was running schools at the time he embarked on his life’s work, he referred to his mammoth scholarship as simply his “hobby.” A decade before his death, he told an Israeli daily newspaper that he hadn’t fully considered the immensity of the work that would be required. He will be remembered for his inspiration, encapsulated with the sentence that when a person knows too much, it may cause him to do nothing, meaning that sometimes it is better not to know too much about the difficulties because it helps focus on the possibilities.