The Modern State of Syria

Modern Syria is a patchwork. Regional and international powers have been present for centuries, at invitation or as occupying forces, in a country comprising a rich mosaic of cultures, religions and ethnicities. This situation—reflected also in other parts of the Middle East—is largely a result of the developments after WWI following the defeat of the Ottoman Empire.

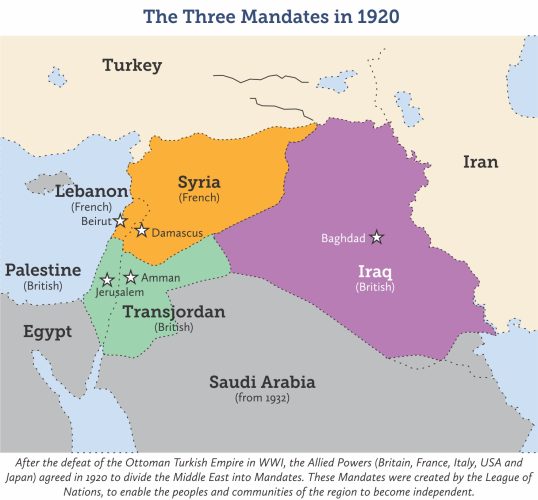

In 1916, as the Ottoman Empire stood on the verge of collapse, the French and British governments agreed on the partitioning of the Middle East. The French would receive the area that roughly overlaps with current-day Syria and Lebanon. This secret Sykes-Picot agreement (named after the civil servants involved) between the French and British would leave a deep and devastating impact on the region. Especially for the Kurds and Syriac-Assyrians, this would have negative consequences up until today.

The Sykes-Picot agreement ultimately superseded the agreements made in 1916 between the British (through their High Commissioner McMahon in Egypt) and Hussein bin Ali Al-Hashimi, the Sharif and Emir of Mecca. Under the McMahon-Hussein agreement, the Arabs were to revolt against the Ottoman Empire with British support and in return the Arabs would establish their independent Arab Kingdom in the Saudi peninsula and Syria and Iraq.

The British essentially promised Syria to two different parties. On the one hand, Syria was to become a French mandate under the Sykes-Picot agreement, and on the other hand part of an independent Arab kingdom. Consequently, the Arabs and French would find themselves at loggerheads over the area.

In 1919 the Syrian National Congress convened and in March 1920 declared Syria as an independent kingdom. That Kingdom (at least on paper) comprised the areas roughly comprising today’s Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Israel. Faisal I bin Al-Hussein (third son of Emir Hussein) was declared King.

While French Prime Minister Georges Clemenceau (1917–1920) was inclined to allow self-rule in Syria, the new French government under Alexandre Millerand based its policy on the Sykes-Picot agreement. As a result, the San Remo Conference of the Allied Powers in April 1920 established a system of mandates as defined by the League of Nations for Palestine, Syria and Mesopotamia.

The Mandate for Syria

In July 1920, the French army took over Syria. Self-rule was replaced by direct colonial rule. The French mandate would create a number of sub-states in Syria that were abolished later on. The one exception was Lebanon which ultimately became an independent state, separate from Syria.

French rule was continuously resisted by the peoples of Syria as became clear in the Great Syrian Revolt (1925–1927), which was supported by all Syrian ethnicities. The French violently cracked down, deploying tactics that would be repeated by the Assad regime in the Syrian civil war after 2011 (including aerial bombardment of civilian areas). However, this revolt led to the realisation in the French government that direct French rule was untenable and that an independent Syria was inevitable. Steps were taken in that direction, but it was only in 1936 that the French and Syrian governments concluded a Treaty in which the French would gradually leave Syria and Syria would become a fully independent member of the League of Nations.

However, this agreement was not immediately implemented, as the Syrian government faced a clash with three regions that demanded greater autonomy. In the coastal western Alawi region, an Alawi movement challenged the central government and so did a Druze movement in the southern Jabal al-Druze region (with As-Suwayda as the regional capital). In both cases, the areas would remain part of Syria.

Moreover, in 1936 an alliance of Kurds and Syriac-Assyrian Christians in cooperation with (a part of the) Arab Shammar tribe drove the call for more regional autonomy for Jazira in North-East Syria, fearing that Damascus would suppress their religious and cultural identity.

Another development that overtook the new government in Damascus was equally a foreshadowing of more recent developments. In 1936 Turkey claimed Hatay (Antioch) and the surrounding Sanjak of Alexandretta. France initially assured that it would not hand it over to Turkey, but ultimately betrayed the Syrian government and in 1938 allowed the Turkish army to enter the Sanjak of Alexandretta. The Turkish army brought also an influx of Turkish citizens who were allowed to vote in an election in the Sanjak which created a regional Parliament that declared independence from Syria. In 1939 this region merged with Turkey. The original Arab and Armenian population fled the area to Syria. This pattern of Turkish occupation and annexation of Syrian territories would be repeated in the Syrian civil war in areas such as Idlib, Afrin, Al-Bab and other areas in northern Syria. In many cases, the Turkish regime would invoke claims stemming from and inspired by Ottoman imperialism.

Both the Hatay crisis and the struggle of autonomist movements (Jazira, Alawi’s and Jabal al-Druze) were evidence that Syria as a political reality was not firmly rooted in all parts of the Syrian state or in the region at large. These crises of the late thirties showed that the institutions of the Syrian state were too weak to maintain the unity of the state. This would prove to be fatal for the Syrian democracy after WWII.

Syrian Independence

In 1946 the French forces finally left Syria, leaving it in the hands of the Syrian government. The years between 1946 and 1961 were marked by political upheaval. Between 1946 and 1956 Syria suffered several coups that (in turn) created a powerful position for the Syrian army. The first coup was in 1949 after Syria lost an unprovoked war against Israel in 1948. This pattern of coups was coupled with increased foreign interference (USSR, Egypt). Pan- Arabism resulted in a temporary political union with Egypt between 1958 and 1961. This ended when the Ba’athists took power through a military coup, caused by the failure of Nasser to implement true power-sharing. In 1970 an intra- party coup brought Hafez-al-Assad to power as de-facto dictator in Syria.

The Assad Dictatorship

The state that the Assads presided over never truly accepted totalitarian rule. The fact that an Alawi clan wielded absolute power over all of Syria was unacceptable for many, as became clear in the uprisings and resistance against the Assad regime over the years. The clearest example was the ‘Islamist uprising’ that culminated in the Hama revolt and subsequent massacre in 1982, in which the Assad regime forces killed thousands of citizens (numbers vary between 10,000 and 40,000). Ultimately the prospect of a small Alawi elite forever maintaining power over Syria was not realistic. Initially, Bashar al-Assad seemed to understand this when he took power following his father’s death in 2000 and opened up some dialogue with opposition leaders, but that window closed soon after. Ultimately Syria could not escape from the Arab uprisings of 2011 against dictatorial regimes in the region, which were the beginning of the notorious Syrian civil war.

The Assad regime would have been defeated without the substantial support from Russia and Iran, which enabled the regime to cling to power in around two-thirds of Syria. This left

Russia and Iran practically in de-facto control over areas nominally ruled by Assad. The Sunni Arab population may have been militarily defeated but continuing protests and flare-ups between 2020 and 2021 (especially in Daraa) indicated that only sheer force kept Assad in power.

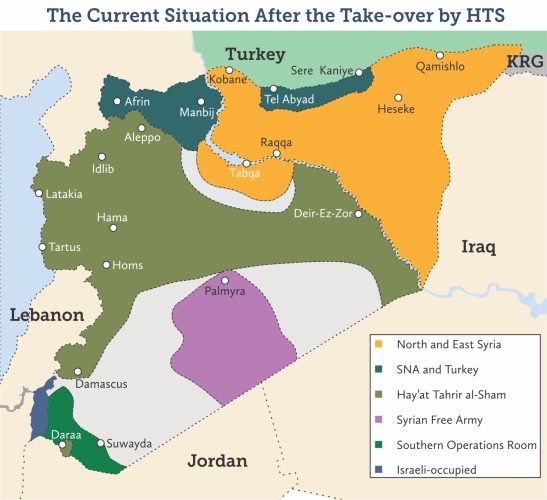

Thus, by the end of 2024 and before the fall of Assad, there were roughly four types of territorial control in Syria: those areas under the control of the Assad regime, the areas under the control of Turkey, areas occupied by Turkey, and the AANES region in NE Syria defended by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

The Current Situation in Syria

The most acute situation in Syria is the possible return of ISIS if Turkey’s aggression against north-east Syria is not stopped. The return of ISIS would lead to new chaos in Syria and mean a potential resurgence of civil war. Without the SDF, there will be no more than a local force to fight ISIS in Syria.

Damascus was not taken by HTS but by the Syrian Free Army (coming from US base ‘Al Tanf’ on the border with Jordan) and the Southern Operations Room (amalgamation of resistance forces from Daraa and As Suweida (Druze city)).

Syrian Democratic Forces, Southern Operations Room and Syrian Free Army are arguably multi-ethnic and multi-religious and anti-extremist. SDF has played a major role in defeating ISIS. Southern Operations Room is partially Druze and has already publicly called for good relations with Israel. Syrian Free Army was part of the fight against ISIS along with US for years. Because of its size, the HTS has been able to establish an interim administration in Damascus that (unlike AANES) does not currently include ethnic/religious minorities.